Delirium And Bipolar

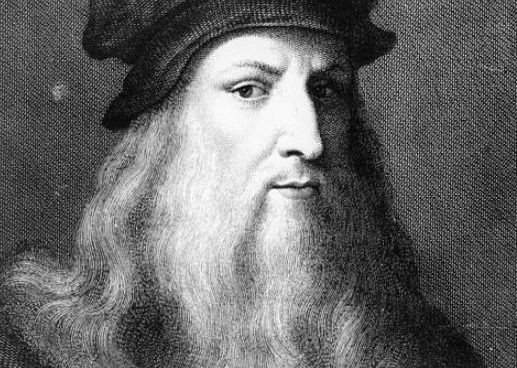

“For once you have tasted flight you will walk the earth with your eyes turned skywards, for there you have been and there you will long to return. ” – Leonardo da Vinci.

Our patient a 29-year-old, graduate from middle socioeconomic status and urban Asian background. He had a two-year history of episodic illness with interepisodic premorbid level of functioning. Earlier two episodes of mania of very high severity resolved rapidly, with treatment. When normal, he used to stop medication. He was completely off psychotropic medication for six months before the current episode.

He presented with an acute onset, third episode, of ten-day duration, characterized by assaultive behaviour, incessant and boastful talk, excessive planning, overfamiliarity, increased sexual desire, and decreased need for sleep and food. He was continuously reciting from the holy books; his relatives saw no coherence in it; it was totally misplaced. He engaged in continuous charity, without any signs of stopping it. The symptoms increased in severity within the previous six hours.

Delirium is a medical condition characterized by a vascillating general disorientation, which is accompanied by cognitive impairment, mood shift, self-awareness, and inability to attend (the inability to focus and maintain attention). The change occurs over a short period of time— hours to days— and the disturbance in consciousness fluctuates throughout the day.

Along with these symptoms, for previous ten days, our patient was confused, had forgetfulness for recent events, and was not able to consistently identify even his close family members. He was seeing images of snakes on fans and would become extremely fearful. He was sometimes urinating and defecating inside the house, and in his clothes.

Due to the fact that the patient is unable to attend consistently to his environment, he/she can become disoriented. Nevertheless, disorientation and memory loss are not essential to the diagnosis of delirium; the inability to focus and maintain attention, however, is essential to rendering a correct diagnosis. Left unchecked, delirium tends to transition from inattention to increased levels of lethargy, leading to torpor, stupor, and coma. In its other form, delirious patients become agitated and almost hypervigilant, with their sleep-wake cycle dramatically altered, fluctuating between great guardedness and hypersomnia (excessive drowsiness) during the day and wakefulness during the night. Delirious patients can also experience hallucinations of the visual, auditory, or tactile type. In such cases, the patient will see things others cannot see, hear things others cannot hear, and/or feel things that others cannot, such as feeling as though his or her skin is crawling.

The findings in the physical examination, including a detailed neurological assessment, were unremarkable. He was exhausted; however, there were no signs of dehydration.

Just as the ingestion of certain drugs may cause delirium in some patients, the withdrawal of drugs can also cause it. Alcohol is the most widely used and most well known of these drugs whose withdrawal symptoms may include delirium. Delirium onset from the abstinence of alcohol in a chronic user can begin within three days of cessation of drinking. The term delirium tremens is used to describe this form of delirium. The resulting symptoms of this delirium are similar in nature to other delirious states, but may be preceded by clear-headed auditory hallucinations. In other words, the delirium has not begun, but the patient may experience auditory hallucinations. Delirium tremens follow and can have ominous consequences with as many as 15% dying.

Some of the structural causes of delirium include vascular blockage, subdural hematoma, and brain tumors. Any of these can damage the brain, through oxygen deprivation or direct insult, and cause delirium. Some patients become delirious following surgery. This can be due to any of several factors, such as: effects of anesthesia, infections, or a metabolic imbalance.

Infectious diseases can also cause delirium. Commonly diagnosed diseases such as urinary tract infections, pneumonia, or fever from a viral infection can induce delirium. Additionally, diseases of the liver, kidney, lungs, and cardiovascular system can cause delirium. Finally, an infection, specific to the brain, can cause delirium. Even a deficiency of thiamin (vitamin B1) can be a trigger for delirium

Rapport could not be established. He was extremely agitated, cursing everybody, including the doctors, and spitting at others. He even assaulted the hospital staff. He was turning everything upside-down, pushing the hospital furniture, jumping on the bed, dragging the mattresses, destroying all that which was in his reach. He had to be tied securely to the cot, but was even pulling the cot. He was making sexual advances towards fellow patients and hospital staff. These prolonged periods of extreme agitation would be followed by brief periods of sudden calmness and muteness.

Symptoms of delirium include a confused state of mind accompanied by poor attention, impaired recent memory, irritability, inappropriate behavior (such as the use of vulgar language, despite lack of a history of such behavior), and anxiety and fearfulness. In some cases, the person can appear to be psychotic, fostering illusions, delusions , hallucinations, and/or paranoia . In other cases, the patient may simply appear to be withdrawn and apathetic. In still other cases, the patient may become agitated and restless, unable to remain in bed, and feel a strong need to pace the floor.

He was continuously talking, loudly, some meaningless and mostly incoherent words. There was echolalia, echopraxia, stereotypy, word salad, flight of ideas, and clang associations. He was having delusions of grandiosity with mood congruent delusions of persecution and reference. He believed that he was God’s messenger, with a mission to eradicate suffering and could communicate with others by telepathy. He strongly suspected that his neighbours were discussing his greatness. He had second person auditory hallucinations and would hear threatening voices of devils, which were envious of his power and wanted to kill him by sending secret executioners. He had visual hallucinations and could see images of snakes sent to execute him. He believed that the treating psychiatrists were butchers sent by persecutors to finish him off. He demonstrated extreme fluctuations of mood, ranging from extreme dysphoria to infectious jocularity. He would suddenly burst into tears. He was confused and had fluctuating levels of consciousness. He was inattentive, disoriented in time, could not recognize his family members, and said that he was in a railway station. His insight into his illness was impaired.

A phrase often used to describe delirium is “clouding of consciousness,” meaning the person has a diminished awareness of their surroundings. While the delirium is active, the person tends to fade into and out of lucidity, meaning that he or she will sometimes appear to know what’s going on, and at other times, may show disorientation to time, place, person, or situation. It appears that the longer the delirium goes untreated, the more progressive the disorientation becomes. It usually begins with disorientation to time, during which a patient will declare it to be morning, even though it may be late night. Later, the person may state that he or she is in a different place rather than at home or in a hospital bed. Still later, the patient may not recognize loved ones, close friends, or relatives, or may insist that a visitor is someone else altogether. Finally, the patient may not recognize the reason for his/her hospitalization and might accuse staff or others of some covert reason for his/her hospitalization (see example below). In fact, this waxing and waning of consciousness is often worse at the end of a day, a phenomenon known as “sundowning.”

There was no history of medical (including hypertension and other cardiovascular disorders) or neurological disorders, or substance abuse. There was no history to suggest infection in recent past. His elder sister was suffering from bipolar disorder, but was never treated.

While the symptoms of delirium are numerous and varied, the causes of delirium fall into four basic categories: metabolic, toxic, structural, and infectious. Stated another way, the bases of delirium may be medical, chemical, surgical, or neurological. Many metabolic disorders, such as hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, hypokalemia, anoxia, etc. can cause delirium.Other metabolic sources of delirium involve the dysfunction of the pituitary gland, pancreas, adrenal glands, and parathyroid glands. It should be noted that when a metabolic imbalance goes unattended, the brain may suffer irreparable damage.

One of the most frequent causes of delirium in the elderly is overmedication. The use of medications such as tricyclic antidepressants and antiparkinsonian medications can bring about an anticholinergic toxicity and subsequent delirium. In addition to the anticholinergic drugs, other drugs that can be the source of a delirium are:

- anticonvulsants, used to treat epilepsy

- antihypertensives, used to treat high blood pressure

- cardiac glycosides, such as Digoxin, used to treat heart failure

- cimetidine, used to reduce the production of stomach acid disulfiram , used in the treatment of alcoholism

- insulin, used to treat diabetes

- opiates, used to treat pain

- phencyclidine (PCP), used originally as an anesthetic, but later removed from the market, now only produced and used illicitly

- salicylates, basically found in aspirin

Laboratory studies, including complete blood picture, renal functions, blood sugars, liver and thyroid functions, urine analysis, chest X ray, and electro-cardiogram did not reveal any abnormalities. A brain computed tomography and serum creatinine phospho kinase (CPK) estimation could not be done as the family members were unwilling because of financial constraints.

He was diagnosed to have “bipolar disorder I, most recent episode manic, severe with psychotic features” as per Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM IV criteria). He had associated features suggestive of delirium.

Whether or not delirium is diagnosed in a patient depends on the type manifest. If the case is an elderly, postoperative patient who appears quiet and apathetic, the condition may go undiagnosed. However, if the patient presents with the agitated, uncooperative type of delirium, it will certainly be noticed. In any case, where there is sudden onset of a confused state accompanied by a behavioral change, delirium should be considered. This is not intended to imply that such a diagnosis will be made easily.

Frequent mental status examinations, at various times throughout the day, may be required to render a diagnosis of delirium. This is generally done using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). This abbreviated form of mental status examination begins by first assessing the patient’s ability to attend. If the patient is inattentive or in a stuporous state, further examination of mental status cannot be done. However, assuming the patient is able to respond to questions asked, the examination can proceed. The Mini-Mental State Exam assesses the areas of orientation, registration, attention and concentration, recall, language, and spatial perception. Another recently evaluated and recommended tool for use in diagnosing delirium is the Delirium Rating Scale-Revised-98. This clinician-rated, 16-item scale allows for the assessment of 13 severity items and three diagnostic items. This test has been reported as more sensitive than the MMSE at detecting delirium.

At times, the untrained observer may mistake psychotic features of delirium for another primary mental illness such as schizophrenia or a manic episode such as that associated with bipolar disorder . However, it should be noted that there are major differences between these diagnoses and delirium. In people who have schizophrenia, their odd behavior, stereotyped motor activity, or abnormal speech persists in the absence of disorientation like that seen with delirium. The schizophrenic appears alert and although his/her delusions and/or hallucinations persist, he/she could be formally tested. In contrast, the delirious patient appears hapless and disoriented, between episodes of lucidity. The delirious patient may not be testable. A manic episode could be misconstrued for agitated delirium, but consistency of elevated mood would contrast sharply to the less consistent mood of the delirious patient. Once again, delirium should always be considered when there is a rapid onset and especially when there is waxing and waning of the ability to attend and the confusion state.

Since delirium can be superimposed into a pre-existing dementia , the most often posed question, when diagnosing delirium, is whether the person might have dementia instead. Both cause disturbances of memory, but a person with dementia does not reflect the disturbance of consciousness depicted by someone with delirium. Expert history taking is a must in differentiating dementia from delirium. Dementia is insidious in nature and thus progresses slowly, while delirium begins with a sudden onset and acute symptoms. A person with dementia can appear clear-headed, but can harbor delusions not elicited during an interview. One does not see the typical fluctuation of consciousness in dementia that manifests itself in delirium. It has been stated that, as a general rule, delirium comes and goes, but dementia comes and stays. Delirium rarely lasts more than a month.

Treating delirium means treating the underlying illness that is its basis. This could include correcting any chemical disparities within the body, such as electrolyte imbalances, the treatment of an infection, reduction of a fever, or removal of a medication or toxin.

Delirium is one of the oldest forms of mental disorder known in medical history.